1) Supply & Demand Dynamics: seasonality, inelastic demand, and volatility

The economics in a paragraph

Agricultural supply is biologically constrained and seasonal; demand for staples is relatively inelastic. Together, these two characteristics produce acute price volatility when supply shocks (droughts, pests, trade bans) strike or when demand shifts (biofuel policy, animal feed demand). Storage, finance and market institutions are the main tools economists use to smooth the intertemporal mismatch between harvest surpluses and lean-period needs.

Why this matters in 2025

The FAO Food Price Index and other global indices have shown significant swings over recent years — peaks in 2022 after the Ukraine shock, with elevated but variable levels through 2024–2025. Even when global averages moderate, specific commodities (vegetable oils, sugar, some cereals) remain volatile due to weather and trade dynamics. Policymakers in both producing and importing countries still wrestle with short-term interventions (export bans, buffer stock releases) that stabilize domestic prices but can amplify global volatility. Reuters+1

Example — the mechanics at harvest

When a bumper wheat harvest arrives but storage/market access is poor, many smallholders sell immediately at low prices to cover household expenses and debts. Where rural finance, warehouse receipt systems and commodity exchanges are weak, harvest gluts translate into farmer distress today and food price spikes tomorrow. So the economics of the harvest window — timing, credit, storage — is a core mechanism shaping farmer incomes.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Invest in rural storage, timely price information, and affordable short-term credit. Use a combination of transparent buffer stock policies and targeted safety nets instead of knee-jerk export bans that increase global price uncertainty.

2) Productivity & Technology: closing yield gaps without sacrificing sustainability

The economics in a paragraph

Raising yields (productivity per hectare or per unit input) is the fastest route to increasing rural incomes and food availability without converting more land to agriculture. But the return on technology depends on access, scale, and the ecological footprint. The challenge is sustainably closing the “yield gap” — the difference between current yields and what is agronomically feasible.

Why this matters in 2025

Technologies are maturing quickly: precision agriculture, drones, better genetics and digital advisory services are all tangible options for raising yields and reducing input waste. Drone use alone has surged: industry reports in 2024–2025 indicate millions of ag-drones in service globally and dramatic year-over-year growth in regions that can afford them. But adoption is uneven; without appropriate financing and service models, many smallholders are excluded. DJI Official+1

Case study — precision & service models for smallholders

Large farms can buy tractors and GPS equipment; smallholders can benefit from service providers: cooperatives or local service entrepreneurs offering drone spraying, soil testing, and pay-per-use precision services. Economically, pay-for-service reduces upfront capital constraints and widens the adoption net—if the provider model is viable and there is demand aggregation.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Focus public R&D on locally adapted varieties and extension; support private-sector service models that deliver precision tech to smallholders; pair technology adoption with finance, training and farmer organizations.

3) Farm Labor Economics: mechanization, migration and the future workforce

The economics in a paragraph

Labor economics in agriculture sits at the intersection of technology and structural transformation. Mechanization boosts productivity but can reduce labor demand; migration (seasonal and permanent) reallocates labor across sectors; and demographic shifts influence who remains in farming.

Why this matters in 2025

Mechanization continues to spread — not only tractors but harvesters, automated irrigation and, increasingly, drones. Where off-farm employment has not expanded sufficiently, mechanization without alternative job creation can depress rural incomes and raise social tensions. Conversely, mechanization that replaces very arduous tasks can free up young people to pursue higher-value activities in farming (horticulture, agri-entrepreneurship). Policymakers must coordinate mechanization policies with rural job strategies. World Bank

Case study — staged mechanization + rural non-farm jobs

Successful transitions often couple equipment pools or rental markets with investments in agro-processing facilities that create local employment — keeping value addition and jobs in rural areas. For instance, community-level machine-hiring services (custom hiring centers) reduce the need for every household to buy expensive equipment while maintaining local demand for machine operators and technicians.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Design mechanization rollouts with rural employment strategies: skill development, agro-processing investments, and machine-rental schemes reduce negative labor impacts.

4) Land, Tenure & Scale: smallholders, consolidation, and digital titling

The economics in a paragraph

Land rights and farm size shape incentives to invest, ability to access credit, and the economics of mechanization. Fragmentation limits scale economies; strong tenure unlocks investment; well-designed rental markets let land be managed efficiently without displacing vulnerable occupants.

Why this matters in 2025

Digitization of land records is accelerating in many countries, reducing disputes and enabling collateralized lending. Where land markets remain opaque, credit is expensive and investments in soil health, irrigation or trees are less likely. At the same time, the economics of consolidation is changing as service models (contract farming, FPOs) can deliver scale benefits without large land transfers.

Example — digital titling and finance

Where governments create clear, digital land registries and mobile interfaces for land information, banks are more willing to offer loans backed by land titles or warehouse receipts. That reduces the cost of capital for productivity investments and allows farmers to adopt longer-term, higher-return practices.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Prioritize secure, inclusive digital land records; support voluntary aggregation and FPOs so smallholders can reach scale economics while retaining ownership.

5) Trade, Markets & Globalization: comparative advantage, standards and shocks

The economics in a paragraph

Trade allows countries to specialize and consumers to benefit from lower prices and variety. But agriculture’s perishability, SPS (sanitary and phytosanitary) requirements, and political sensitivity make trade complicated. Export bans, unpredictable tariffs and geopolitical shocks (e.g., war, sanctions) transmit rapidly into domestic markets.

Why this matters in 2025

Global food price indices and trade flows have been sensitive to macro shocks. In 2022–2025, trade disruptions and weather events created headline volatility in specific commodities (vegetable oils, cereals). Policymakers face the classic tradeoff: insulate domestic consumers with restrictions (which can backfire) or keep borders open and use targeted safety nets to protect the poor. Reuters+1

Case study — oilseeds & feed markets

Oilseed markets (soy, rapeseed) underpin both edible oil supplies and feed for livestock. A country relying heavily on imports is exposed to global price shocks; building domestic crushing/processing capacity reduces vulnerability and can capture value domestically. But this requires infrastructure, credit and quality standards.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Pursue predictable trade policies and invest in domestic processing capacity; use trade to diversify suppliers and avoid single-source dependencies that create risk.

6) Food Security & Nutrition Economics: calories vs. diets and social protection

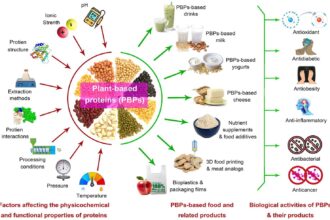

The economics in a paragraph

Food security has three pillars — availability, access, and utilization (nutrition). Agricultural policy that focuses only on calories or production of staples can neglect diet quality and micronutrient deficiencies. Social protection instruments (cash transfers, school feeding) can be powerful complements to agricultural policy.

Why this matters in 2025

Global production has generally kept up with demand, but distributional gaps, price spikes and quality issues persist. International policy research emphasizes the need to align agricultural incentives with nutrition goals — incentivizing more pulses, vegetables and animal-source foods, while ensuring affordability for low-income households. IFPRI and others have recommended more integrated policies linking agriculture and nutrition. IFPRI

Case study — linking procurement to nutrition

Programs that purchase fruits and vegetables from local smallholders for school feeding create demand stability and improve child nutrition. The economic multiplier: steady local demand raises farmer incomes and reduces post-harvest losses for perishable crops when collection and cold-chain logistics are well-designed.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Design policies that encourage production and market access for nutrient-dense foods and pair subsidies/price supports with nutrition objectives.

7) Government Policy & Subsidies: distortions, targeting and reform pathways

The economics in a paragraph

Governments globally use subsidies, price supports and procurement to stabilize incomes and ensure food security. But poorly targeted subsidies create distortions (overuse of fertilizer, groundwater depletion), fiscal stress, and inequitable benefits to larger farmers. The economics of reform emphasizes targeted transfers, sequencing, and investment in public goods as complementary measures.

Why this matters in 2025

Many countries are debating subsidy reforms and more cost-effective targeting mechanisms (direct benefit transfers, index-based insurance). The World Bank and other institutions have advocated for shifting resources from universal subsidies to public goods (research, extension, infrastructure) and better-targeted social protection. World Bank

Example — fertilizer and electricity subsidies

Fertilizer subsidies can boost short-term yields but undermine soil health and promote imbalanced nutrient use. Electricity subsidies for pumps have driven groundwater overextraction in many regions. Reform strategies combine gradual price adjustments, compensated by targeted transfers and investments in efficient irrigation.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Sequence reforms carefully: build markets, finance, and safety nets before removing broad subsidies; replace inefficient universal supports with targeted programs and public goods.

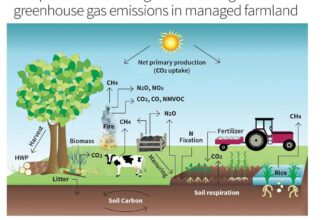

8) Environment, Water & Climate Economics: natural capital, incentives and PES

The economics in a paragraph

Agriculture depends on natural capital — soil, water, biodiversity — but agricultural practices can erode these assets. Economics provides tools: pricing scarce resources (water), payments for ecosystem services (PES), carbon credits, and regulation to internalize externalities.

Why this matters in 2025

Climate impacts are already visible — heat stress, changing monsoon patterns, and more frequent extreme events — making adaptation and mitigation critical. COP-era commitments and carbon markets are starting to include agriculture, but designing equitable payments and reliable MRV (measurement, reporting, verification) systems is hard. IPCC and FAO analyses point to the need for “climate-smart agriculture” approaches that bundle adaptation and mitigation. FAOHome+1

Case study — payments for ecosystem services

When farmers are paid to maintain wetlands, plant agroforestry or practice conservation tillage that sequesters carbon, they receive income while public goods (biodiversity, carbon sinks) are preserved. The economic challenge is verifying outcomes and making sure payments reach smallholders fairly.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Design PES and carbon programs with simple, verifiable metrics and include aggregation mechanisms so smallholders can access payments.

9) Value Chains, Logistics & Post-Harvest Losses: aggregation, cold chains & market power

The economics in a paragraph

Value chain efficiency determines how much of the consumer price reaches the farmer. Post-harvest loss in perishables is a huge invisible tax on farmer incomes and food availability. Aggregation (FPOs), cold chains, better packaging and digital marketplaces reduce loss and increase farmer value capture.

Why this matters in 2025

Cold chain investments, refrigerated transport and pack-houses are increasingly recognized as high leverage. Public support, concessional finance and PPPs have catalyzed investments in some regions. However, consolidation in processing and retail can concentrate market power, potentially squeezing farmgate prices unless producers organize. World Bank

Case study — cold chains for horticulture

Where countries have built cold chain corridors connecting production hubs to urban demand centers, farmers saw better prices for perishable crops and lower seasonal gluts. The economics here is straightforward: reducing loss raises effective supply and raises returns to farmers and processors.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Promote FPOs and aggregation; incentivize private investment in cold chains; regulate market power while enabling scaling and quality control.

10) Future Shocks & Transformations (2025–2050): digital data, urban farming and scenarios

The economics in a paragraph

Future agricultural economics will be shaped by data ownership, digital platforms, alternative proteins, urban and vertical farming, and the resilience of long supply chains to shocks (pandemics, geopolitical events). The governance of data and equitable distribution of digital rents will be central economic questions.

Why this matters in 2025

Digital tools — precision sensors, blockchain traceability, AI forecasting — are already changing production and markets. Who captures the value? Companies with data and platform control, or farmers who own their records? Drone adoption and platform growth are visible signs of rapid technical change. IFPRI and other institutions highlight the need for policy frameworks to ensure inclusive digital transitions. IFPRI+1

Three scenario sketches to guide thinking

- Inclusive Technology & Sustainable Intensification: public investment plus private-sector service models lead to higher yields, lower emissions and better farmer incomes.

- Polarized Gains: tech primarily benefits larger farms; smallholders are marginalized, producing political and social backlashes.

- Localized Resilience & Short Chains: emphasis on local systems and urban farming reduces exposure to global shocks but limits economies of scale.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Create data governance rules, support farmer-centric platforms, invest in rural broadband and use scenario planning to design flexible policies and investment plans.

Synthesis — how these ten economics interact

These ten forces are not independent — they interact constantly.

- Storage and finance (1) determine whether productivity gains (2) translate into better incomes or just larger harvest-time gluts.

- Land tenure reforms (4) unlock productivity and adaptation investments (2 & 8).

- Trade policy (5) can amplify or dampen domestic price signals that influence cropping choices and nutrition (6).

- Value-chain investments (9) change who captures value and can offset the negative distributional effects of mechanization (3) by creating local processing jobs.

- Environmental payments (8) can compensate farmers for practices that otherwise reduce short-term income but deliver public goods.

For analysts and policymakers the bottom line is coordination: subsidies, infrastructure, digital policies and market regulation need to be treated as a package, not as isolated interventions.

Practical recommendations (policy, private sector & farmers)

For policymakers

- Prioritize public goods: R&D, extension, rural roads, storage and digital infrastructure. (These underpin many other levers.)

- Sequence subsidy reform: build targeted safety nets and finance before removing inefficient universal subsidies.

- Invest in climate-resilient R&D and index-based insurance systems with transparent data.

- Strengthen land records, promote voluntary aggregation, and protect tenant/women’s rights.

- Enable predictable trade policies and invest in domestic processing capacity to reduce vulnerability.

For agribusiness & investors

- Invest in service models that deliver precision agriculture to smallholders (equipment-as-a-service, drone services, soil testing labs).

- Finance cold chains and aggregation centers with PPP models and risk-sharing mechanisms.

- Build farmer-centric digital platforms that offer transparent pricing and fair contract terms.

For farmers & farmer organizations

- Use aggregation (FPOs) to capture scale economies and bargaining power.

- Explore machine hire services to access mechanization without heavy capital outlay.

- Leverage digital price and weather information to time sales and inputs better.

- Consider diversifying to nutrient-dense or higher-value crops where market access exists.

Closing reflections

The economics of agriculture in 2025 is a mixture of old truths (seasonality and inelastic demand) and new realities (fast digital adoption and intensifying climate risks). Policy choices made today — on data governance, subsidy design, investment in rural infrastructure and inclusion strategies for technology — will determine which of the future scenarios unfold. The most resilient path blends productivity growth with social protection and environmental stewardship. That requires honest trade-offs, careful sequencing of reforms, and a focus on institutions that can coordinate the complex economics of food systems.

Key sources (for verification and deeper reading)

- FAO — Food Price Index and FAOSTAT (food price trends and statistics). FAOHome+1

- Reuters news summary of FAO index and 2025 price trends. Reuters

- World Bank — Agriculture overview, investments, and policy guidance. World Bank

- IFPRI — Global Food Policy Report (2024–2025 series) and policy recommendations. IFPRI+1

- Industry/technology snapshot — ag-drone adoption reports (DJI, 2024–2025 summaries). DJI Official+1

- Analysis pieces on farmer mobilizations and policy dynamics (e.g., India farmers’ protests, policy effects). The Diplomat+1

If you’d like, I can next:

- Convert this into a fully formatted 5,000-word HTML article with H1/H2/H3 tags and embedded citation links;

- Produce a downloadable PDF or MS Word file optimized for your CMS;

- Expand any single section into a deep dive with district-level examples, charts and country case studies (e.g., India, Brazil, US).

Which would you like me to do now?The economics in a paragraph

Agricultural supply is biologically constrained and seasonal; demand for staples is relatively inelastic. Together, these two characteristics produce acute price volatility when supply shocks (droughts, pests, trade bans) strike or when demand shifts (biofuel policy, animal feed demand). Storage, finance and market institutions are the main tools economists use to smooth the intertemporal mismatch between harvest surpluses and lean-period needs.

Why this matters in 2025

The FAO Food Price Index and other global indices have shown significant swings over recent years — peaks in 2022 after the Ukraine shock, with elevated but variable levels through 2024–2025. Even when global averages moderate, specific commodities (vegetable oils, sugar, some cereals) remain volatile due to weather and trade dynamics. Policymakers in both producing and importing countries still wrestle with short-term interventions (export bans, buffer stock releases) that stabilize domestic prices but can amplify global volatility. Reuters+1

Example — the mechanics at harvest

When a bumper wheat harvest arrives but storage/market access is poor, many smallholders sell immediately at low prices to cover household expenses and debts. Where rural finance, warehouse receipt systems and commodity exchanges are weak, harvest gluts translate into farmer distress today and food price spikes tomorrow. So the economics of the harvest window — timing, credit, storage — is a core mechanism shaping farmer incomes.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Invest in rural storage, timely price information, and affordable short-term credit. Use a combination of transparent buffer stock policies and targeted safety nets instead of knee-jerk export bans that increase global price uncertainty.

2) Productivity & Technology: closing yield gaps without sacrificing sustainability

The economics in a paragraph

Raising yields (productivity per hectare or per unit input) is the fastest route to increasing rural incomes and food availability without converting more land to agriculture. But the return on technology depends on access, scale, and the ecological footprint. The challenge is sustainably closing the “yield gap” — the difference between current yields and what is agronomically feasible.

Why this matters in 2025

Technologies are maturing quickly: precision agriculture, drones, better genetics and digital advisory services are all tangible options for raising yields and reducing input waste. Drone use alone has surged: industry reports in 2024–2025 indicate millions of ag-drones in service globally and dramatic year-over-year growth in regions that can afford them. But adoption is uneven; without appropriate financing and service models, many smallholders are excluded. DJI Official+1

Case study — precision & service models for smallholders

Large farms can buy tractors and GPS equipment; smallholders can benefit from service providers: cooperatives or local service entrepreneurs offering drone spraying, soil testing, and pay-per-use precision services. Economically, pay-for-service reduces upfront capital constraints and widens the adoption net—if the provider model is viable and there is demand aggregation.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Focus public R&D on locally adapted varieties and extension; support private-sector service models that deliver precision tech to smallholders; pair technology adoption with finance, training and farmer organizations.

3) Farm Labor Economics: mechanization, migration and the future workforce

The economics in a paragraph

Labor economics in agriculture sits at the intersection of technology and structural transformation. Mechanization boosts productivity but can reduce labor demand; migration (seasonal and permanent) reallocates labor across sectors; and demographic shifts influence who remains in farming.

Why this matters in 2025

Mechanization continues to spread — not only tractors but harvesters, automated irrigation and, increasingly, drones. Where off-farm employment has not expanded sufficiently, mechanization without alternative job creation can depress rural incomes and raise social tensions. Conversely, mechanization that replaces very arduous tasks can free up young people to pursue higher-value activities in farming (horticulture, agri-entrepreneurship). Policymakers must coordinate mechanization policies with rural job strategies. World Bank

Case study — staged mechanization + rural non-farm jobs

Successful transitions often couple equipment pools or rental markets with investments in agro-processing facilities that create local employment — keeping value addition and jobs in rural areas. For instance, community-level machine-hiring services (custom hiring centers) reduce the need for every household to buy expensive equipment while maintaining local demand for machine operators and technicians.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Design mechanization rollouts with rural employment strategies: skill development, agro-processing investments, and machine-rental schemes reduce negative labor impacts.

4) Land, Tenure & Scale: smallholders, consolidation, and digital titling

The economics in a paragraph

Land rights and farm size shape incentives to invest, ability to access credit, and the economics of mechanization. Fragmentation limits scale economies; strong tenure unlocks investment; well-designed rental markets let land be managed efficiently without displacing vulnerable occupants.

Why this matters in 2025

Digitization of land records is accelerating in many countries, reducing disputes and enabling collateralized lending. Where land markets remain opaque, credit is expensive and investments in soil health, irrigation or trees are less likely. At the same time, the economics of consolidation is changing as service models (contract farming, FPOs) can deliver scale benefits without large land transfers.

Example — digital titling and finance

Where governments create clear, digital land registries and mobile interfaces for land information, banks are more willing to offer loans backed by land titles or warehouse receipts. That reduces the cost of capital for productivity investments and allows farmers to adopt longer-term, higher-return practices.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Prioritize secure, inclusive digital land records; support voluntary aggregation and FPOs so smallholders can reach scale economics while retaining ownership.

5) Trade, Markets & Globalization: comparative advantage, standards and shocks

The economics in a paragraph

Trade allows countries to specialize and consumers to benefit from lower prices and variety. But agriculture’s perishability, SPS (sanitary and phytosanitary) requirements, and political sensitivity make trade complicated. Export bans, unpredictable tariffs and geopolitical shocks (e.g., war, sanctions) transmit rapidly into domestic markets.

Why this matters in 2025

Global food price indices and trade flows have been sensitive to macro shocks. In 2022–2025, trade disruptions and weather events created headline volatility in specific commodities (vegetable oils, cereals). Policymakers face the classic tradeoff: insulate domestic consumers with restrictions (which can backfire) or keep borders open and use targeted safety nets to protect the poor. Reuters+1

Case study — oilseeds & feed markets

Oilseed markets (soy, rapeseed) underpin both edible oil supplies and feed for livestock. A country relying heavily on imports is exposed to global price shocks; building domestic crushing/processing capacity reduces vulnerability and can capture value domestically. But this requires infrastructure, credit and quality standards.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Pursue predictable trade policies and invest in domestic processing capacity; use trade to diversify suppliers and avoid single-source dependencies that create risk.

6) Food Security & Nutrition Economics: calories vs. diets and social protection

The economics in a paragraph

Food security has three pillars — availability, access, and utilization (nutrition). Agricultural policy that focuses only on calories or production of staples can neglect diet quality and micronutrient deficiencies. Social protection instruments (cash transfers, school feeding) can be powerful complements to agricultural policy.

Why this matters in 2025

Global production has generally kept up with demand, but distributional gaps, price spikes and quality issues persist. International policy research emphasizes the need to align agricultural incentives with nutrition goals — incentivizing more pulses, vegetables and animal-source foods, while ensuring affordability for low-income households. IFPRI and others have recommended more integrated policies linking agriculture and nutrition. IFPRI

Case study — linking procurement to nutrition

Programs that purchase fruits and vegetables from local smallholders for school feeding create demand stability and improve child nutrition. The economic multiplier: steady local demand raises farmer incomes and reduces post-harvest losses for perishable crops when collection and cold-chain logistics are well-designed.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Design policies that encourage production and market access for nutrient-dense foods and pair subsidies/price supports with nutrition objectives.

7) Government Policy & Subsidies: distortions, targeting and reform pathways

The economics in a paragraph

Governments globally use subsidies, price supports and procurement to stabilize incomes and ensure food security. But poorly targeted subsidies create distortions (overuse of fertilizer, groundwater depletion), fiscal stress, and inequitable benefits to larger farmers. The economics of reform emphasizes targeted transfers, sequencing, and investment in public goods as complementary measures.

Why this matters in 2025

Many countries are debating subsidy reforms and more cost-effective targeting mechanisms (direct benefit transfers, index-based insurance). The World Bank and other institutions have advocated for shifting resources from universal subsidies to public goods (research, extension, infrastructure) and better-targeted social protection. World Bank

Example — fertilizer and electricity subsidies

Fertilizer subsidies can boost short-term yields but undermine soil health and promote imbalanced nutrient use. Electricity subsidies for pumps have driven groundwater overextraction in many regions. Reform strategies combine gradual price adjustments, compensated by targeted transfers and investments in efficient irrigation.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Sequence reforms carefully: build markets, finance, and safety nets before removing broad subsidies; replace inefficient universal supports with targeted programs and public goods.

8) Environment, Water & Climate Economics: natural capital, incentives and PES

The economics in a paragraph

Agriculture depends on natural capital — soil, water, biodiversity — but agricultural practices can erode these assets. Economics provides tools: pricing scarce resources (water), payments for ecosystem services (PES), carbon credits, and regulation to internalize externalities.

Why this matters in 2025

Climate impacts are already visible — heat stress, changing monsoon patterns, and more frequent extreme events — making adaptation and mitigation critical. COP-era commitments and carbon markets are starting to include agriculture, but designing equitable payments and reliable MRV (measurement, reporting, verification) systems is hard. IPCC and FAO analyses point to the need for “climate-smart agriculture” approaches that bundle adaptation and mitigation. FAOHome+1

Case study — payments for ecosystem services

When farmers are paid to maintain wetlands, plant agroforestry or practice conservation tillage that sequesters carbon, they receive income while public goods (biodiversity, carbon sinks) are preserved. The economic challenge is verifying outcomes and making sure payments reach smallholders fairly.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Design PES and carbon programs with simple, verifiable metrics and include aggregation mechanisms so smallholders can access payments.

9) Value Chains, Logistics & Post-Harvest Losses: aggregation, cold chains & market power

The economics in a paragraph

Value chain efficiency determines how much of the consumer price reaches the farmer. Post-harvest loss in perishables is a huge invisible tax on farmer incomes and food availability. Aggregation (FPOs), cold chains, better packaging and digital marketplaces reduce loss and increase farmer value capture.

Why this matters in 2025

Cold chain investments, refrigerated transport and pack-houses are increasingly recognized as high leverage. Public support, concessional finance and PPPs have catalyzed investments in some regions. However, consolidation in processing and retail can concentrate market power, potentially squeezing farmgate prices unless producers organize. World Bank

Case study — cold chains for horticulture

Where countries have built cold chain corridors connecting production hubs to urban demand centers, farmers saw better prices for perishable crops and lower seasonal gluts. The economics here is straightforward: reducing loss raises effective supply and raises returns to farmers and processors.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Promote FPOs and aggregation; incentivize private investment in cold chains; regulate market power while enabling scaling and quality control.

10) Future Shocks & Transformations (2025–2050): digital data, urban farming and scenarios

The economics in a paragraph

Future agricultural economics will be shaped by data ownership, digital platforms, alternative proteins, urban and vertical farming, and the resilience of long supply chains to shocks (pandemics, geopolitical events). The governance of data and equitable distribution of digital rents will be central economic questions.

Why this matters in 2025

Digital tools — precision sensors, blockchain traceability, AI forecasting — are already changing production and markets. Who captures the value? Companies with data and platform control, or farmers who own their records? Drone adoption and platform growth are visible signs of rapid technical change. IFPRI and other institutions highlight the need for policy frameworks to ensure inclusive digital transitions. IFPRI+1

Three scenario sketches to guide thinking

- Inclusive Technology & Sustainable Intensification: public investment plus private-sector service models lead to higher yields, lower emissions and better farmer incomes.

- Polarized Gains: tech primarily benefits larger farms; smallholders are marginalized, producing political and social backlashes.

- Localized Resilience & Short Chains: emphasis on local systems and urban farming reduces exposure to global shocks but limits economies of scale.

Mini policy/corporate takeaway

Create data governance rules, support farmer-centric platforms, invest in rural broadband and use scenario planning to design flexible policies and investment plans.

Synthesis — how these ten economics interact

These ten forces are not independent — they interact constantly.

- Storage and finance (1) determine whether productivity gains (2) translate into better incomes or just larger harvest-time gluts.

- Land tenure reforms (4) unlock productivity and adaptation investments (2 & 8).

- Trade policy (5) can amplify or dampen domestic price signals that influence cropping choices and nutrition (6).

- Value-chain investments (9) change who captures value and can offset the negative distributional effects of mechanization (3) by creating local processing jobs.

- Environmental payments (8) can compensate farmers for practices that otherwise reduce short-term income but deliver public goods.

For analysts and policymakers the bottom line is coordination: subsidies, infrastructure, digital policies and market regulation need to be treated as a package, not as isolated interventions.

Practical recommendations (policy, private sector & farmers)

For policymakers

- Prioritize public goods: R&D, extension, rural roads, storage and digital infrastructure. (These underpin many other levers.)

- Sequence subsidy reform: build targeted safety nets and finance before removing inefficient universal subsidies.

- Invest in climate-resilient R&D and index-based insurance systems with transparent data.

- Strengthen land records, promote voluntary aggregation, and protect tenant/women’s rights.

- Enable predictable trade policies and invest in domestic processing capacity to reduce vulnerability.

For agribusiness & investors

- Invest in service models that deliver precision agriculture to smallholders (equipment-as-a-service, drone services, soil testing labs).

- Finance cold chains and aggregation centers with PPP models and risk-sharing mechanisms.

- Build farmer-centric digital platforms that offer transparent pricing and fair contract terms.

For farmers & farmer organizations

- Use aggregation (FPOs) to capture scale economies and bargaining power.

- Explore machine hire services to access mechanization without heavy capital outlay.

- Leverage digital price and weather information to time sales and inputs better.

- Consider diversifying to nutrient-dense or higher-value crops where market access exists.

Closing reflections

The economics of agriculture in 2025 is a mixture of old truths (seasonality and inelastic demand) and new realities (fast digital adoption and intensifying climate risks). Policy choices made today — on data governance, subsidy design, investment in rural infrastructure and inclusion strategies for technology — will determine which of the future scenarios unfold. The most resilient path blends productivity growth with social protection and environmental stewardship. That requires honest trade-offs, careful sequencing of reforms, and a focus on institutions that can coordinate the complex economics of food systems.

Key sources (for verification and deeper reading)

- FAO — Food Price Index and FAOSTAT (food price trends and statistics). FAOHome+1

- Reuters news summary of FAO index and 2025 price trends. Reuters

- World Bank — Agriculture overview, investments, and policy guidance. World Bank

- IFPRI — Global Food Policy Report (2024–2025 series) and policy recommendations. IFPRI+1

- Industry/technology snapshot — ag-drone adoption reports (DJI, 2024–2025 summaries). DJI Official+1

- Analysis pieces on farmer mobilizations and policy dynamics (e.g., India farmers’ protests, policy effects). The Diplomat+1